One day ago, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, wrote a very enthusiastic blog post about what he calls the "intelligence age."

In that blog post, he paints a highly optimistic vision of a prosperous future where each human will have a personal AI team working together to create "almost anything we can imagine." Altman expects it to revolutionize teaching—with virtual tutors providing personalized instruction—as well as healthcare, the labor market, and almost every other aspect of life.

Altman’s enthusiastic vision is rooted in the conviction that “deep learning works,” and that by scaling it with more data and more compute, we will be able to achieve artificial general intelligence, the philosopher's stone of AI researchers.

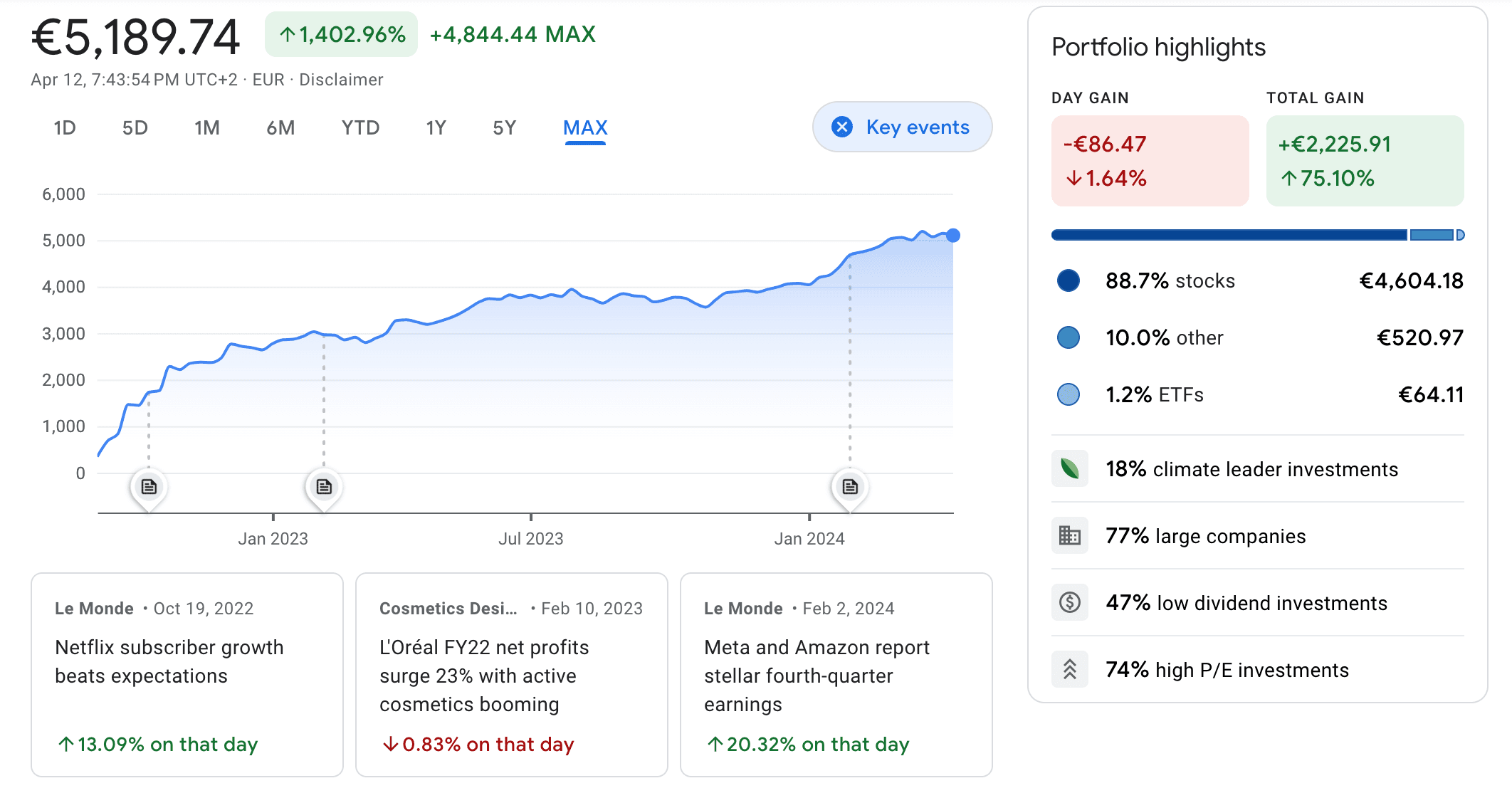

I find Altman’s vision of the future exciting indeed. As a relatively modest player in the ongoing revolution, I do think AI has the potential—and is already, to some extent—boosting human productivity and our ability to accomplish amazing things.

To understand why these times are exciting, let's take a step back and think about the information age. It started in the 1450s with the invention of Gutenberg's printing press, which made the mass production of books—and thus the widespread access to information—possible. The clergy, the rich, and the powerful were no longer the only ones able to access knowledge, and this accelerated the betterment of humanity. It led to the production of more knowledge and more discoveries that globally benefited humanity as a whole.

A lot of the innovation that came after Gutenberg’s printing press—from the telegraph in the 1830s, the telephone in the 1870s, radio broadcasting, computers, and the internet—has acted on three major axes: education—making information easily available, easily shareable, and easily acted upon; work—making tasks easier with personal computing and software to help us quickly make sense of all the information we deal with and make decisions; and leisure—where videos, TVs, computers, and the multimedia revolution have created new ways to be entertained and to entertain others.

I think the intelligence age will see even more improvements in these areas: education, work, and leisure. We are already seeing those impacts. Computers made it easier to access data and perform computations to obtain information. The internet made it easier to share information. Google made it easier to access information in an organized fashion across the internet. AI, and large language models (LLMs) in particular, make it easier to access knowledge—not just information, but knowledge and wisdom, the two highest stages of the DIKW pyramid. But having knowledge and wisdom is not sufficient; we humans still need to act on it to make it useful.

More broadly, AI allows us to access, understand, teach, and create knowledge more easily—given a good dose of critical thinking, especially considering AI’s limitations like hallucinations.

AI allows us to create content (text, audio, images, videos) more easily, which is useful for increasing work productivity (producing reports, presentations, marketing content, emails) and personal productivity (emails, personal assistant tasks, etc.).

AI enables greater productivity at work either by automating content production or by making it easier to acquire knowledge about how to solve problems, thereby simplifying the problem-solving process and making it cheaper and faster.

That is why I am excited about AI. I believe more people should be excited as well.

However, I also acknowledge that many of the things presented in Sam Altman's visionary post might turn out to be wrong. The belief that scaling deep learning models by adding ever more data and more compute will be enough to reach the capabilities necessary to make Altman’s vision possible could be misguided. While I think scaling will continue to help in the near term, I also agree with researchers like Yann LeCun or François Chollet that deep learning doesn't allow models to generalize properly to out-of-distribution data—and that is precisely what we need to build artificial general intelligence. The core test of intelligence is generality: the ability to be applied to every problem, even novel ones. All deep learning models fail at that to some extent. Just look at OpenAI's GPT-4 or o1 preview’s performance on the ARC-AGI test (Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus for Artificial General Intelligence).

Deep learning models will continue to improve as we feed them more data and use more compute, but they will still fail at even very simple tasks as long as the input data are outside their training distribution. The numerous examples of ChatGPT (even the latest, most powerful versions) failing at basic questions or tasks illustrate this well.

Learning from data is not enough; there is a need for the kind of system-two thinking we humans develop as we grow. It is difficult to see how deep learning and backpropagation alone will help us model that. For tasks where providing enough data is sufficient to cover 95% of cases, deep learning will continue to be useful in the form of 'data-driven knowledge automation.' For other cases, the road will be much more challenging.

I am an optimist. I think, in the long run, optimists are more often right than not, at least more so than technology pessimists. I do believe scaling deep learning models will indeed help us do amazing things—from learning faster and better to working more productively. So, if you haven’t already, now is the time to familiarize yourself with AI tools and see how they can make your life a bit better.

I am also a pragmatist and a realist, and I think we will probably need more than deep learning to build AGI.