Africa is not well positioned to rip the benefits of AI. At least for now. It comes from the fact that the culture of collecting data and making decisions based on data is not yet pervasive and often voluntarily so (because who says data says possibility to audit and uncover things people would prefer hidden forever…).

Now I don’t like doing overreaching generalizations when it comes to Africa. Of course, some countries are more advanced (some countries in the Maghreb, a lot of former British colonies, the classic big economic powerhouses — Nigeria, South Africa, etc.). These countries are well positioned to benefit a bit, mostly from domestic R&D, the implementation of classic machine learning algorithms (hello scikit-learn) and maybe a bit of deep learning in some use cases.

Regarding generative AI, the impact will be more direct, because it is a tech easily accessible to the masses via the ChatGPT website or app for example. It could be a force for good, a bit like the internet, wikipedia, or social media have been forces for good by democratising access to information. It can also have negative impacts as large language models can hallucinate and generate false and potentially dangerous answers in domains like healthcare. And with a population often not educated enough, often lacking the critical skills necessary to make the difference, this can lead to poor outcomes. Without the infrastructure to fight it, misinformation can spread faster with dire real life consequences.

So to take advantage of what tools like ChatGPT or what other generative AI tools have to offer, educating the masses about what is possible and what the limitations are, will be important here as in any other part of the world, maybe more than any other part of the world, because of lack of strong institutions to fight misuses.

Anecdote: It’s 2024, and when I return to my native Cameroon, I still have to endure the painful spectacle of snake oil salesmen on private buses, selling solutions that claim to cure 10 to 20 illnesses at once. This is the equivalent of what happened in 18th-century Europe and 19th-century United States. Yet, here we are in the 21st century — can you imagine the gap?

We also have to think about the potential impact on education. AI cheating is difficult to detect, and a lot of African teachers might need upskilling to better understand how to prevent it or even make sure AI tools are used in a way that is beneficial to the overall educational experience. AI detection tools are not efficient and should not be used. They are probably too costly for the average African teacher to use at scale anyway. Low-tech, in-class evaluation, something pervasive and dominant in Africa, can serve as a good temporary solution to curb the dangers of AI cheating. But that obviously does not apply to at-home evaluations.

Overall, in most cases, Africa’s data and tech infrastructures are not ready to maximally take advantage of the AI revolution that is unfolding. Changing that requires a lot of political will and institutional might. As the recent winners of the Nobel Prize in economics, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, have stated in a lot of their research, institutions are the key to why nations succeed or fail. When it comes to the data and AI revolution in Africa, that is even more true.

I always see this talk about Africa leapfrogging this, leapfrogging that. You can’t leapfrog your way out of the fundamentals.

An in AI, the fundamentals are data. If you don’t have the infrastructure, organizational and institutional habit of collecting, curating, and making decisions based on data, you will be limited in the ways in which you can take advantage of AI at scale. This is true for companies and institutions, and it is true for countries.

Without data, African countries will be doomed to use general AI solutions built with EU/US-centric datasets, with maybe a bit of data painstakingly collected from Africa and else.

Those general AI solutions will have the bias that comes from their predominantly US/EU-English datasets. And that’s not even possible for most AI/ML applications that require local data to make any sense.

Let me explain. Let’s take the case of medical diagnosis based on images. It is well known that for some illnesses, learning the symptoms present on black skin is not the same as white skin. That is why there has been a movement in the US to add more black and brown skin in medical textbooks. Now let’s say you train a deep learning model to detect one skin issue and your dataset doesn’t have enough samples of the average African’s skin. The result? A biased model that will certainly have a significantly reduced accuracy if you use it in African countries out of the box and without any localization.

This is not just speculation. Recent studies have shown that AI models used for dermatological diagnosis often fail to perform equally across different skin tones. For instance, algorithms trained predominantly on lighter skin have been found to misdiagnose or overlook conditions on darker skin. In a Northwestern University study, AI-assisted diagnoses improved overall accuracy but widened the gap between diagnoses for lighter and darker skin, especially among primary care physicians. Furthermore, a review of dermatology AI models found that many were not trained on diverse datasets, leading to misdiagnoses for people with darker skin tones, especially in detecting conditions like skin cancer.

New study suggests racial bias exists in photo-based diagnosis despite assistance from 'fair' AI

That’s the kind of issues African countries might have to face in the future. And it is just the tip of the iceberg.

Hopefully there are a lot of personal and corporate initiatives to bridge the gap. It’s a good start, but I fear that without the proper institutional might, the relative impact of these initiatives might stay small or not large enough to prevent the inevitable gap that will widen between EU/US/Asia and Africa because of AI.

There is no leapfrogging possible. Start with the data infrastructures.

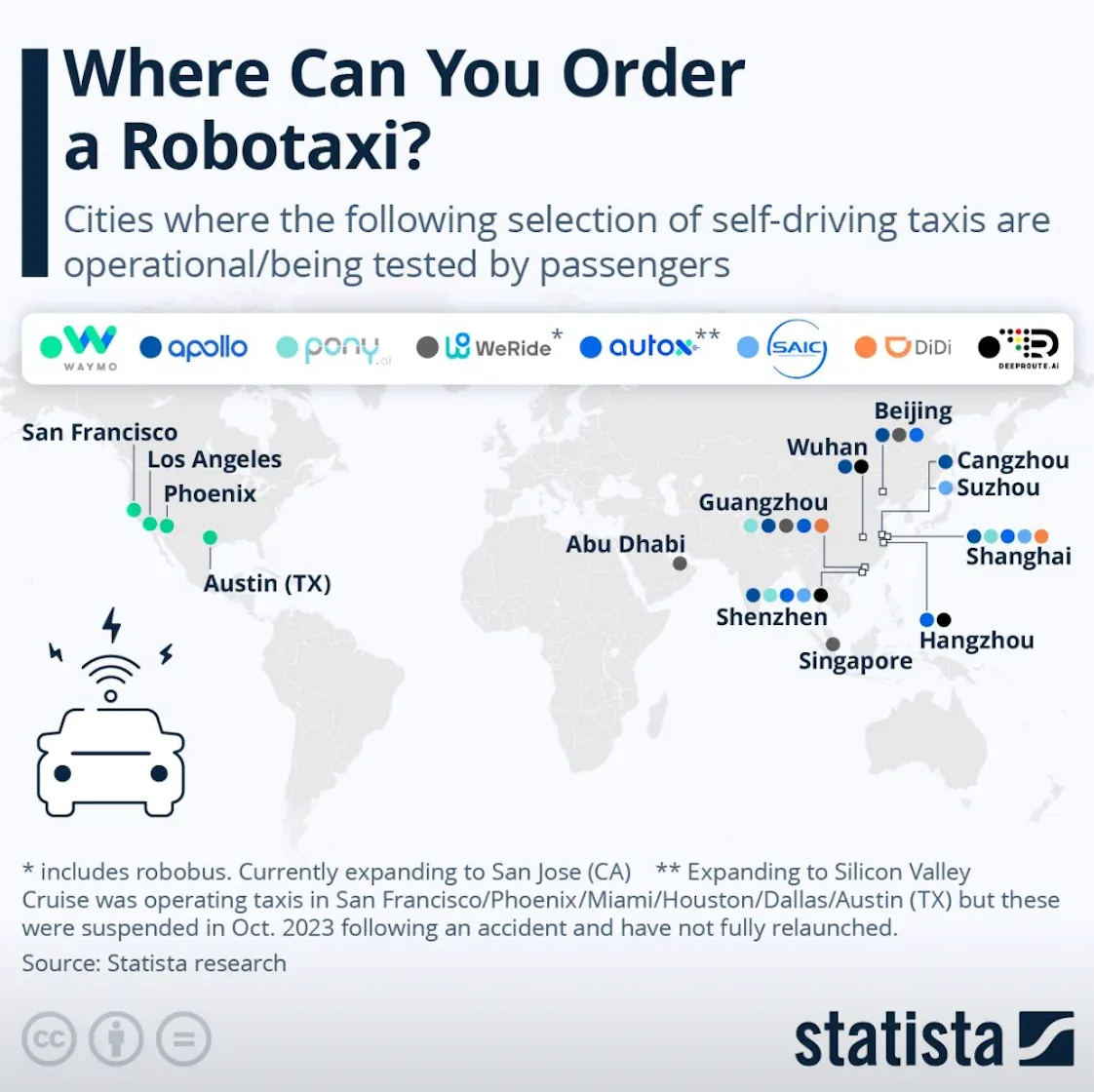

Small analogy to finish: Here is a map of the places where you can order a robotaxi in 2024. This is one of the most fascinating use cases of AI. There are not a lot of cities in Europe or Africa where it’s possible (to put it mildly).

A tale of robotaxis

What should African countries do? Start thinking about their robotaxi strategy or maybe focus on building enough roads, the proper addressing system, etc.?

You know the answer.

I argue that African countries should have the same approach for all AI use cases.